Keegan Monaghan

Artist in Residence

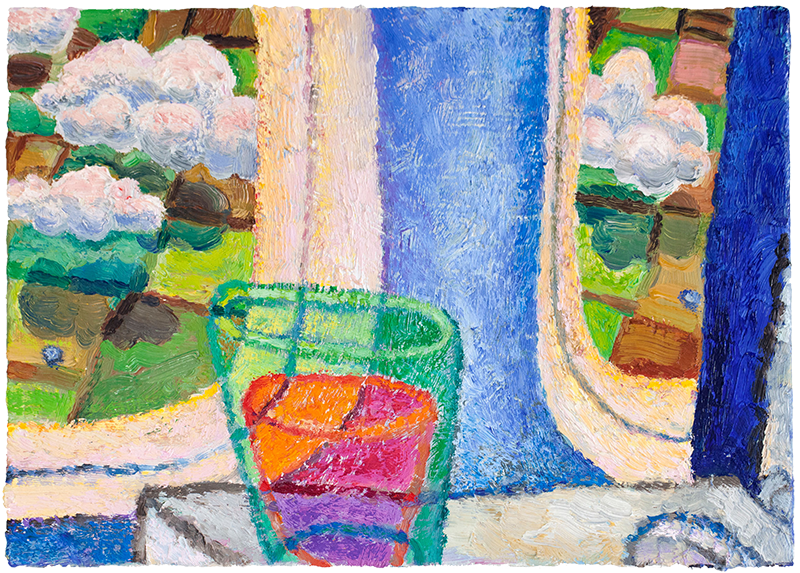

Born in 1986 in Evanston, IL, Keegan Monaghan currently lives in Brooklyn, NY. His paintings evoke the partial experience of looking, contrasting the subjectivity of first-person perspective with competing, inter-locking fields of vision which proliferate in the contemporary environment. These are represented by apertures, screens and frames, implied or literal, which enact emotional tensions between what is visible and what is excluded. With these junctures in mind, Keegan describes the paintings as depicting, “dramatic states of immersion, absorption or alienation.” He develops the composition of each painting as he works. Editing them over a long period of time, their surfaces become highly textured. He says that this approach, “infuses the paintings with a psychological edge which evokes a certain clock-ticking anxiety and doubt.”

Keegan attended The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York, NY. Recent solo exhibitions in New York, NY are Incoming, James Fuentes (2018); You decide to take a walk, On Stellar Rays (2016); and Total Recall, OLD ROOM (2015). Recent group exhibitions include Whitney Biennial, The Whitney Museum for American Art, New York, NY (2019); Eighteen Hundred Showers, Simone Subal Gallery, New York, NY (2018) and Gallery Four, Baltimore, MD (2017).

During his residency in Spoleto Monaghan made a series of new paintings, including several made ‘en plain air’, and created an installation of ceramic sculptures in the roadside chapel Madonna del Pozzo, under the invitation of local curator Franco Troiani. In a conversation with curator Guy Robertson, reproduced below, he discusses his experience of working in Spoleto and his approach to painting.

Guy Robertson: How did it feel unwrapping the pictures you’d made in Spoleto when you got them back to the US?

Keegan Monaghan: It was a strange sensation to unwrap and look at these paintings in my studio in Brooklyn. Aside from the difference in scale (my paintings are usually much larger) the paintings felt more immediate, which I think was part of their original conception. I wanted to make a group of paintings that came from looking at the town of Spoleto and the odd angles of buildings and the light and the shapes of trees. There were some recurring themes in these paintings that have showed up in my other work, mainly the motif of the window, but these paintings felt less psychologically fraught. I think it had to do with the fact that I was viewing this residency as an escape from New York. It’s also a result of the time I had to work on these paintings. They were much less worked and I think they feel fresher and less anxious as a result.

GR: In Spoleto we referred to some of the paintings as postcard paintings: you painted the aqueduct, views from a window or a balcony. Do they feel like souvenirs?

KM: I think they do kind of function like souvenirs. I hung up two paintings by my worktable in my studio and they feel like snapshots. For the most part, these paintings were all done from memory and imagination but they come from looking at the town. I felt very inspired by the light and the textures of the buildings and the shapes of the cypress trees. Everything seemed to be visually interesting and I felt like just reacting to that was as good a reason as many to make a painting. And it’s true, I was thinking of them as these kind of personal mementos that would mean something else to me when I got home and looked at them.

GR: The aqueduct painting totally changed when you added the spotlights.

KM: Aside from the plein air paintings I made at Casa Mahler, the painting of the aqueduct was the closest one to a life painting. I saw the aqueduct at least once a day and I knew I wanted to make a painting of it as a kind of homage to Turner’s painting of the same aqueduct. I would make very quick sketches while looking at the structure—for the other paintings I didn’t really make sketches based on specific scenery, it was more of an amalgamation. For a while the painting of the aqueduct was a day scene and I felt self-conscious that it felt too traditional and quaint. Adding the spotlights meant turning the day scene into a night scene, based on an impression of how I remembered the light looking on the structure, and it became a lot more evocative while also becoming less realistic. I think in a way these paintings are trying to represent the kind of distortion that occurs in memories.

GR: It was fascinating revisiting your studio throughout the five-week residency and seeing the paintings evolve. In the rooftop painting the angles of the nearest roof-tiles were raised to the horizontal, to give us a sense of looking over and beyond. Whilst in the painting with the grilled window you eventually added the balcony with the green chair, and the painting clicked. These changes are about situating our gaze, setting up how they eye travels through the painting. It’s interesting how these manipulations affect the emotional impact of the painting.

KM: I’m a very slow painter. Even these paintings, which I intentionally tried to make fast, took the entire residency to complete and, if there wasn’t the deadline of returning home to Brooklyn, I’m sure I’d still be working on them. But it can be extremely freeing and even generative to have a deadline, no matter how real or imagined it is. I often feel like the entire process of making a painting is an extended state of trying to fix what I’ve done wrong. It almost feels paradoxical, like I’m trying to figure out what I want by an almost endless amount of discovering what I don’t want it to be. In this way, the image of the painting is actually growing out of every mark and wrong move. I don’t scrape off the parts, I paint over—I let them come through and add to

the colour, the surface and the general psychology of the image. Hopefully, if I’m sensitive to all of these moving elements, I’ll know when I make the right move. But painting is a strange and obscure thing and I still feel mystified by it.

GR: You once said to me that it’s easy to get fixated with a part of the painting which is working — the nose on a person’s face, was the example you gave — but then the whole painting starts to revolve around the success of that part, to the detriment of the rest of the canvas.

KM: Yes, this is something I’m always trying to be aware of while painting. I often find that once I’m working around a section of a painting in that way, the surrounding parts start to feel self-conscious and stiff. For me, the solution is usually to paint over the nose, or whatever it is that I’m working around. Fortunately, I’m interested in what happens to the colour and shape and texture as these things get built up and painted over again and again.

GR: The texture of each painting is made up of multiple gestural marks. A gestural mark by its nature looks unfinished, unresolved, it fluctuates. For me, the malleability that you describe paint as having, the ability to edit and adjust, echoes the fluidity of human feelings and makes it a useful medium for describing emotions. When this dynamic, expressive quality of paint is coupled with memory—the painting as a souvenir, trying to recapture and understand an experience—as well as the shifting, inter- locking perspectives of the contemporary environment (the feeling we have, often because of technology or travel and migration, that the authentic ‘experience’ is located somewhere else—something which I think your paintings dramatise very succesfully), you have an even more powerful medium. Are your paintings primarily trying to express feelings?

KM: My main goal is to make emotional work that depicts shared feelings. It’s a slow process of decision making—stepping back to see the effect, pictorially as well as emotionally. To make a yellow mark and stand back and try to understand how the emotional tonality just changed or if anything has happened at all. It’s not always so clear. Obviously the representational aspect of the image plays a huge role in what the painting is about and how it works, but I think that there is a parallel quality that is more abstract and much harder to define. In part it has to do with the psychology of working and reworking an idea, and the way this obfuscates the image.

GR: Can you discuss the ceramics you made for the roadside chapel Madonna del Pozzo [pictured above]? How did they come about and how do they relate to your sculptural work and the paintings?

KM: I wanted to use the kiln that was in the cantina and I thought the ceramics could be a good counterpoint to my painting practice. I like the relationship that ceramics have with time—they’re made very fast, in one sitting, which feels related to the plein air paintings I was also making. There’s also a very literal connection between the impressionistic quality of the thumbprints in the ceramic work and the brush marks in my paintings. Originally, the ceramic fruit was supposed to sit in a big bowl, which was made in the same impressionistic manner. It blew up in the kiln but ultimately I think the piece made entirely more sense laid out and arranged on the altar. When we were offered the Madonna del Pozzo to show work in, I knew I wanted to make something that acknowledged this very specific and unique space. I loved the idea of making something that had its own light source and which was time based and also performative. It was also something that alluded to ritual and the nature of the chapel, which is how I arrived at the candle. Then there was this idea of an offering to the space and I was interested in how alien these shiny warped forms would look juxtaposed in the ancient space with the fresco as a backdrop.

GR: Broadly speaking, what have you taken from the experience of your residency?

KM: This was the first and only residency I have done and it was extremely inspiring. The experience has definitely planted a strong desire to designate more time to paint in different places around different people with different constraints. I hope to do more residencies, especially ones outside of the US.