Lewis Chaplin

b. 1992, London, England

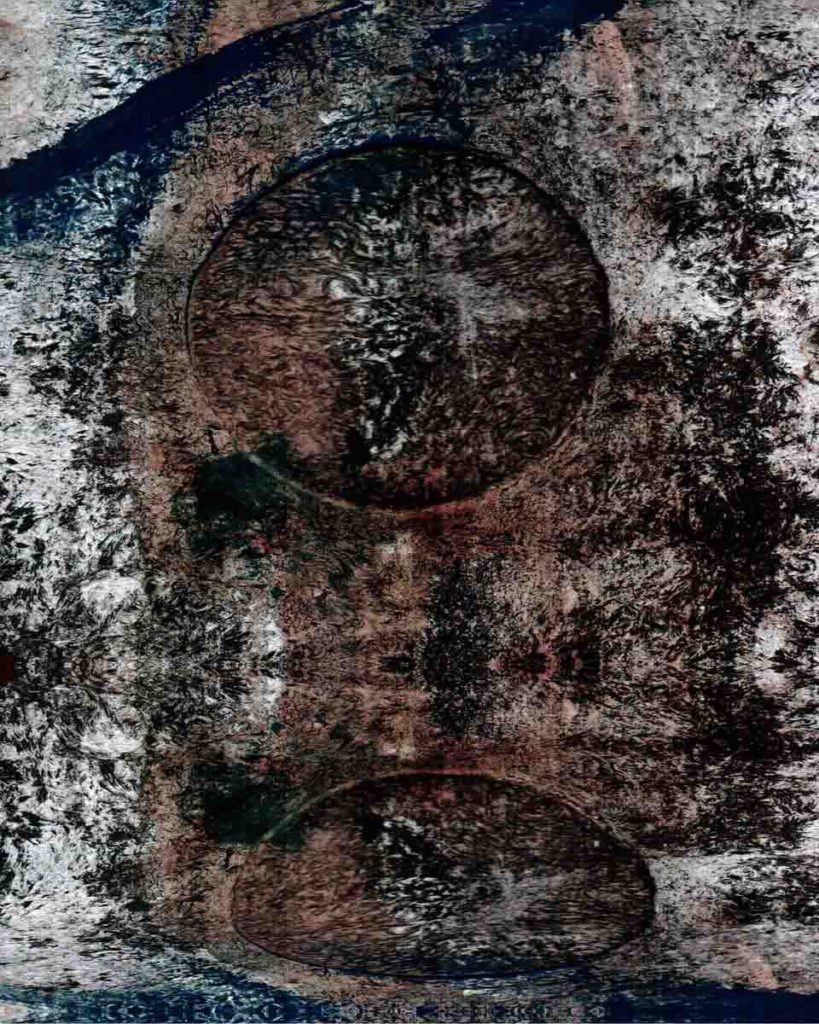

Above: Detail of Chaplin’s installation in the Lavatoio San Marco, Spoleto.

Lewis Chaplin is an artist and publisher based in London. His practice is informed by his studies in anthropology at Goldsmiths College. During his residency in Spoleto he worked on several book projects, whilst exploring new image-making techniques with a hand-held document scanner. His experiments culminated in an exhibition at the Lavatoio San Marco as well as a new sound piece. Giovanni Rendina, our curator-in-residence who worked closely with Chaplin, conducted the conversation reproduced here.

INTERVIEW WITH LEWIS CHAPLIN

By Giovanni Rendina

Giovanni Rendina: Could you tell me about the hand-held scanner you’ve been experimenting with during your residency?

Lewis Chaplin: I first started seeing these scanners in image archives — they are essentially the head of a flatbed scanner on wheels, intended for the easy and immediate recording of documents. I’ve been thinking about the scanner as a site of production for a while — it feels like everything passes through it, whether analogue or digital, and that the act or even gesture of scanning is one that feels synonymous with everyday life: the brief overview, the glimpse, and the flattening that occurs when things are rendered digitally. A scanner is really just another type of camera and so I began to use the hand-held scanner like it was one, trying to give it some agency. I took it out onto the streets and started to use it as an image-making tool, recording the surfaces around me.

GR: There’s a strong performative component to this technique, which is very different from photography: for example, the gesture as you drag the scanner across different surfaces.

LC: The most interesting thing about the hand-held scanner is how the image-making act lies somewhere between a physical, embodied gesture and an industrial, mechanical process. In Spoleto I found that I could ‘draw’ with the scanner — by manipulating direction, speed and position — and compose new images from everyday surfaces. I like it because it compresses the performance of photography into something very dense: you are physically touching the surface you wish to represent. In one respect the resulting image is therefore very close to being a faithful, ‘unmediated’ representation — nodding to that secret desire of photography to be a pure mirror of the world. However, the hand corrupts that desire very easily, making it messy again.

At the same time as making these scanner images, I was also always recording sound. A piece started to emerge in which recordings of walking, scanning, talking, typing, scribbling — the city and the studio — were woven through each other, creating a dense layer of sound. In a similar way to the scanner, I was attempting to sculpt and manipulate existing features of the city and my studio, in this case auditory, and to draw attention to process. It actually acted as a counter-balance to the flattening that happens with the scanner.

GR: At the end of your residency you exhibited some of the images you’d been making, can you tell me about that?

LC: Whilst walking around making images with the scanner, I came across an abandoned 18th century wash-house. It has four deep pools, overflowing and covered in moss, with graffiti all over the walls. It was exactly the kind of densely layered and slightly decrepit place that suited my use of the scanner. I was also particularly drawn to the sound, which is cavernous and full of the echo of four dripping taps, one for each pool.

I printed around twenty-five scanner images onto blue-back flyposting paper and then wheat pasted them directly to the walls of the wash-house. It was an interesting doubling of the gesture and process of scanning. Not only was I literally embedding the prints back into the wall but, working against the dirty, cobwebbed and crumbling building, I found myself thigh-deep in filthy water, covered in wheat paste and using my hands to spread it all over the images, rather than a brush which became too filthy. This had an extremely tactile and caring feel to it, as my hands continually caressed the prints, a bit like scanning; I moulded them to every imperfection and dent in the wall. It felt very intimate and sensuous. All the rejected prints were sunk into the pools. These display methods were unexpected and exciting. I’d like to expand on this more performative element.

Something else unexpected happened during the ‘Viggiatori sulla Flaminia’ event at the end of the session. At dusk we walked a large group of people down to the lavatoio and used flashlights to illuminate the space. The audience assisted us and our shadows were cast across the water. The fact that the audience had to discover the space through their own light sources felt very atmospheric.

GR: How does this way of working relate to your practice more broadly?

LC: My initial interest in the hand-held scanner came out of a book project I’ve been making in and around my studio in South Bermondsey, London, which looks at the successive layers of industrial development in that area. During my research I was handed a portable scanner by a librarian so I could make a copy of an archival image of slum dwellings that stood on the land where my studio was later built.

Broadly, I work with images. Sometimes I make my own photographs, sometimes I work with other people’s images. Often I combine the two. Generally I’m trying to harness photography to tell stories about the world, or to interrogate the ways in which images shape the way we tell those stories.

GR: So you see yourself as a storyteller?

LC: Yes. My academic background is in anthropology, a discipline which uses data, gathered through experience, to tell or unpick stories that exist in particular places. When it is successful, it manages to make those local stories function as allegories for larger concepts or ideas. In my practice, storytelling doesn’t have to be as explicit as in anthropology (which is often closer to documentary), but I am always looking for ways where you can use something small and immediate to talk about something larger.

GR: The anthropological approach can be distant and cold, since the researcher must adopt an impartial position. How do you deal with this? Is there a place for personal emotions in your work?

LC: Yes, for anthropologists there is a tension between the embodied experience of fieldwork and the subsequent effort to synthesize this research, smoothing out its contours and turning it into something analytical. I wouldn’t call an anthropological approach distant though — it certainly was back in the day, when it was about measurements, charts and diagrams — but modern anthropology, or at least the type I’m interested in, is personal, reflexive, narrative based, and more in line with storytelling. Maybe it is better to say that the research is “reliant on gathering information through experience”, rather than data, which sounds like you’re handing out a questionnaire.

What I have always liked about anthropology is how ruthlessly self-reflexive and self-critical it is. Anthropological writing often draws your attention to the tools and methods through which it tries to produce knowledge and authority. It critiques those tools (the main tool being anthropologists themselves). That’s something I often find myself drawn to when I’m working with pictures — to try and make visible the tools and constraints through which the pictures have been made, as these tools often tell a story in themselves.

GR: The way in which you manipulate, extract and compose from archives is another important aspect of your work.

LC: Yes. Often my point of departure for a project is found in an archive — I tend to start by trawling existing sources before thinking about how I can layer my own approach onto that.

GR: So there is at first an analytical, deconstructive approach — as you assess the materials — and then a constructive and more intimate one which follows?

LC: It’s not as simple as deconstructing the meaning or nature of an image and then moving onto the next stage. The process seems like one that is constantly shifting or in progress, like a game.

Vilem Flusser expressed this well. His idealised, critical photographer is one that can outwit the camera‘s rigidity and ‘smuggle human intentions into its program’. It sounds like a game of cat and mouse, or something sneaky and devious, which I like. Often I’m looking to find the human dynamics or unpredictable qualities that are hiding in a photographic tool. The archive is one of those tools, and it led me to these hand-held scanners.

Lewis Chaplin is an artist and publisher based in London. His most recent artist book, 2041, is published by Here Press and is a collaboration with an anonymous concealment fetishist. Chaplin has a major, ongoing project about Tristan da Cunha—the world’s most remote inhabited island— and it was the subject of a recent exhibition at Roaming Projects in London. Alongside Sarah Piegay Espenon, Chaplin he runs Loose Joints, an independent publishing house and design studio. They have published books by Oliver Griffin, Harley Weir, Richard McGuire, Marton Perlaki, Samarra Scott and Sean Vegezzi. From 2009 to 2014, Chaplin co-ran Fourteen Nineteen with Alex F. Webb, a project dedicated to supporting young photography. He was also an organiser of the Copeland Book Market, an annual event for printed matter which ran from 2010–2015. www.lewischaplin.com