HAVE GOTTEN SOME IDEAS FOR NEW WORK …

Daniela Ruiz Moreno, Joshua Leon and Abbas Zahedi, Spring Session 2022

At the Torre Bonomo, curator in residence Daniela Ruiz Moreno led co-residents and artists Joshua Leon and Abbas Zahedi in a conversation about art and social practice, caring and hosting, mental health, art residencies and the town of Spoleto. As part of their practice, all three work closely with communities. In Madrid, for example, Daniela curates ‘Cuidadorxs Invisivble’, developing projects with people suffering from degenerative diseases and their carers; with his ‘Sonic Support Group’, Abbas held art therapy sessions during the pandemic with NHS and frontline workers. Joshua’s recent work exploring olive cultivation in Spoleto, meanwhile, invites local audiences to engage in conversations around society and ecology. The following is an excerpt from an hour long conversation.

Abbas Zahedi: As a caregiver you have to be attentive and respond to a person’s needs. The situation is constantly changing. It’s difficult to plan long term, as everything is in the present. That was my reality during my childhood, my ground of development, and it really influenced this idea of having a ‘practice’. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that I went from studying medicine to art, and that doctors and artists both have a practice. As artists engaging directly with people, there’s a lot of change and a lot of responding to things that can throw you off. However, if you come back to this kind of weird umbrella term, practice, it helps you to pull things back in and take stock of what’s actually taking place.

Joshua Leon: The role of caregiver requires flexibility and a commitment to hosting, you develop a practice but it isn’t formulaic. Rather, it’s a constant awareness that things will change. So you are asking yourself, how can I be prepared to change or be in a constant state of change? When you’re working in that way, you are opening yourself up. Instead of having a conversation at an audience, you’re actually in a conversation. You’re not giving people a lecture, you are waiting, as much as anything, for other people, spaces and objects to speak back. Often it can be quite a challenge – you can be met by silence. But when you’re constructing this kind of flexible framework, you start to work with the idea that you can occupy the space where silence occurs. Things will start to speak if you trust them to. I was asked recently, ‘what do I need for my practice?’ It made me reflect on the importance of taking care of yourself in a practiced way, to understand when you need more time, more energy, input from new voices and so on. […] With attention, you can develop a kind of motion inside yourself that opens things up. Often it doesn’t happen as you expect, and that’s something which you have to understand and you need to be self aware and self critical. It’s almost like you are making a passage.

AZ: I like that word passage because what we are really dealing with is the passage of time. The three of us live in metropolitan centres, Madrid and London; places where it is hard to be aware of the passage of time. We have talked a lot about why so many artists have found the Mahler & LeWitt Studios an inspiring place: it is because time feels different here. In the city, you check the time, you don’t see it. In Spoleto, we see time. Looking out across this table, I can see a medieval city tucked into ancient mountains. At one point in the 10th century the valley was a swamp – this is extraordinary transformation, and you can understand it because you can visualise it. You can also see modernity in Spoleto: the friction between the old city and the new city, for example.

From this perspective in particular, on top of the Torre Bonomo, you can see the horizon and how the sun moves. Day to day: you’re aware of time. You see the moon: month to month. Every year there’s a an arts festival in Spoleto and we’re very aware of that: you go out to eat in the restaurants and you see the annual poster commissions hung on the walls. You’re constantly bathed in time. You’re living in a kind of chamber resonating with many different voices and you can channel energies from different eras – you understand a sense of continuity that exists, but which often isn’t experienced. In our practices, I think we try to resist the lack of continuity that we are forced to deal with in modern environments, or in hyper neoliberal, ultra-capitalist society.

JL: Situating yourself in what I call ‘slow time’, is a way of resisting being consumed. The urban environment wants to speed everything up. Essentially, slowing down means working more methodically. Time itself is one of the most consuming elements. You start your day and it’s 8:30 and then suddenly it’s five in the afternoon and you’re asking yourself what you achieved. During my residency in Spoleto, I really produced a lot, but I still had time to nap every day! It’s funny, but maybe I really needed some rest and somehow through rest, I actually produced the same as I would normally produce. There’s something to be said for that, sometimes we get lost in this idea of, ‘oh, I have to be producing’, which is a consumptive behavior. If you step outside of that for a day, a week, a month – if you get given an opportunity to come to Spoleto, for example – your body clock changes. It’s an opportunity to host yourself.

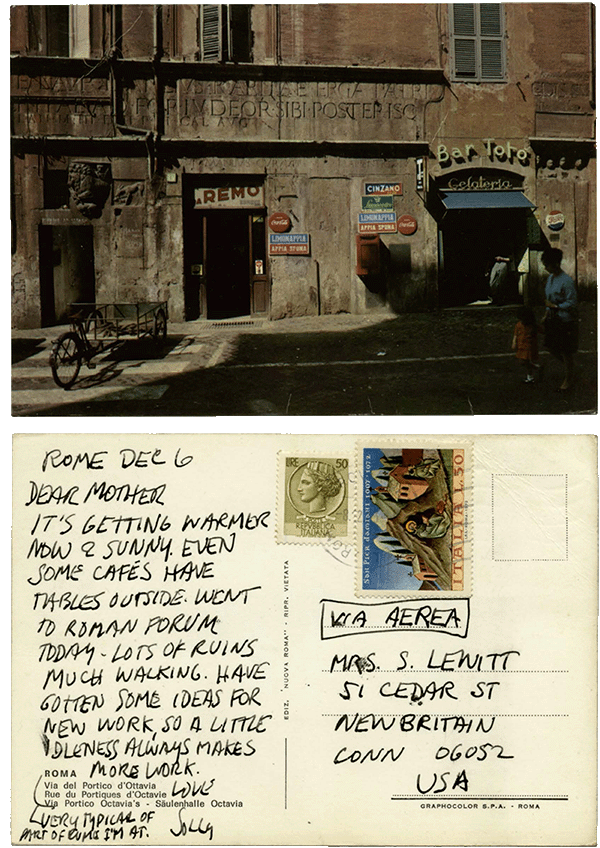

Daniela Ruiz Moreno: I read a postcard that Sol LeWitt wrote to his mother from Spoleto. He uses this word “idleness”. After describing his tourist excursions around Rome, he concludes, “Have gotten some ideas for new work, so a little idleness always makes more work.” I really like that and I think that’s really in the spirit of what a residency such as this one can help produce.

As soon as I arrived in Spoleto, I felt a difference in how I consumed information. Even the tone of my voice changed. Your body starts to mirror or become affected by the environment. There is a fight with a more rational part of myself that wants to analyze that response. There is something to be said for letting go of this rational approach and to embrace your body as a kind of receptor, a very smart, sophisticated and environmentally aware receptor. In the curatorial projects I run involving artists and caregivers, I find it useful to think of ourselves as a kind of antenna, because you’re constantly having to be receptive to the needs of the group and your impact on the tone that is being collectively created. It has a lot to do with listening.

[…]

JL: The way to investigate Spoleto is to talk to people, or to talk to the buildings or to the trees. It sounds mad to say, ‘talk to the trees’, but that’s the way you’re going to understand Spoleto. We are fortunate in that we have the Mahler & LeWitt Studios curators as translators, they have a huge amount of knowledge, but there are other people. If you go to Caffe Artisti in the Piazza del Mercato and you speak to the people who work there, they’ll give you a completely different context of how Spoleto runs. Generally, there’s this joyousness to their everyday labor. They love making you coffee. They love making you a sandwich, and they smile about it.

AZ: I think that’s the key, it’s love. The Mahler & LeWitt Studios has a lot of love in it. There is a love in the dialogue with artists, with art and with the history of Spoleto as a space for the arts. I think that is really the element that is not reproducible – which moves away from a rarefied, elusive or exclusive take on art. The feeling of trying to embody a space through a process of care, love and hosting, has a value that is very hard to convey. The program here is focussed on research and development, so there is very little expectation in terms of outcomes. I think that is a dream scenario for artists, to be in a place where you say, ‘actually, now I can’t…’. It’s like you’re tuning an instrument. I was working in Casa Mahler and I heard this crazy abstract music coming from the music room – singular notes reverberating. I was like, who is this musician?! It felt like a Fluxus thing, really experimental. But then I realised it was the piano tuner. It made me think of this analogy and how your body, in a sense, is an instrument that needs tuning. You rely on your senses. It’s what you work with. Even if you make work on a computer, you’re still using your hands and there’s an embodiment. You rely on the things you have at your disposal in terms of your bodily and mental capacities. They need attention in a way that this residency can provide.

JL: When you take away the expectation of making, outcomes increase in a different way. If you remove expectation, people don’t stop producing. You almost produce more because you start to develop your own criteria for what is expected of yourself. This process of managing expectations and understanding your personal routine and best practice of working, is extremely important.