Keeping Time, online

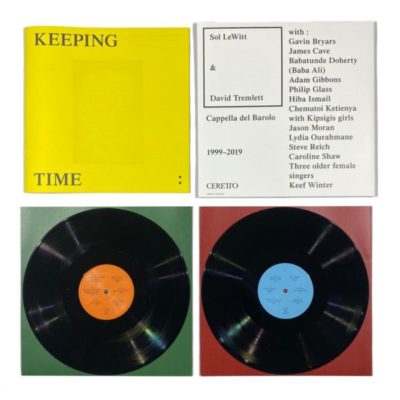

published by Ceretto in collaboration with the Mahler & LeWitt Studios, curated by Guy Robertson and Tony Tremlett

Through the rhymes and rhythms of music, the Keeping Time vinyls celebrate 20 years of the Cappella del Barolo, a countryside chapel in the Langhe in Piedmont painted and pastelled by Sol LeWitt and David Tremlett.

Please visit www.ceretto.com for more information about the chapel. Scroll down for an introduction to the vinyls by the project curators. For more information about the connected residency, exhibition and performance program click here >>.

The three tracks with an × next to their titles are not included in the online mix for licensing reasons.

Purchase a hard-copy of the record >>

Click here for extensive program notes for each track >>

SIDES A and B, 1950—2002 look at musicality in LeWitt and Tremlett’s work by delving into their own extensive music collections and finding affinities between their visual art and the work of their composer friends and contemporaries.

A

David Tremlett & Tim Bowman

Prelude

2’15”

Gavin Bryars

Cage du Grand Escalier

8’03”

David Tremlett & Tim Bowman

Still Life

3’32”

Sol LeWitt

Art by Telephone

1’32”

Three older female singers ×

Piedmont: Nen Maria nostra frighietta

2’00”

Chemutoi Ketienya with Kipsigis girls ×

Chemirocha III

1’29”

B

Steve Reich

Clapping Music

3’37”

Philip Glass

Part I: Music in Twelve Parts

16’06”

David Tremlett & Tim Bowman

Pastlude

2’00”

SIDES C and D, 2012—2019 a younger generation of artists related to the work of LeWitt and Tremlett either with direct responses or through their exploratory combinations of visual art and architecture, with music and performance.

C

Adam Gibbons

Intro O

0’49”

Keef Winter

Appropriate Energy

3’38”

Hiba Ismail

SUNKAB ![]()

0’45”

Babatunde Doherty (Baba Ali)

Itinerant’s Creed

4’58”

Lydia Ourahmane

Akfadou

4’11”

Caroline Shaw ×

Limestone & Felt

5’42”

D

Adam Gibbons

Intro O

0’49”

James Cave

The Point on the Arch Mid-Way Between the Two Walls

5’57”

Hiba Ismail

![]()

2’16”

Jason Moran

If The Land Could Tell

8’09”

KEEPING TIME

Tony Tremlett and Guy Robertson

We begin with a chapel. It is found in a grid of vineyards, stitched to the rolling hills of the Langhe in Piedmont, Northern Italy. Although it looks baroque, the Cappella del Barolo was built in the early part of the twentieth century. It was never consecrated, and farmhands used it as a shelter from the elements. We can imagine that folk music and cattle bells would have met the ears of passersby more often than evensong. Over the course of the century the countryside depopulated and the chapel was left to ruin until it was restored in 1999 by Bruno Ceretto, a farmer and winemaker who had acquired the vineyards amongst which the chapel stood. Wishing to celebrate the land on which his business was dependent, whilst offering it something new and culturally meaningful, Ceretto decided to commission an artwork for the restored chapel. It was through his invitation that Sol LeWitt and David Tremlett came to paint and pastel the chapel and start a new chapter in its history.

In contrast with the earthy palette of the landscape, LeWitt painted the exterior of the chapel in bold colours using geometric and curvilinear forms. Exuberant and joyful, it is a beacon for the tens of thousands who seek it out each year. The doors of the chapel are always open, and once inside, the visitor finds an intimate and reflective space whose colours echo those of the land. Its inlaid stone floor, stained glass windows, and pastel walls and ceilings were assembled by Tremlett. The chapel is unique in LeWitt’s oeuvre as his only wall drawing to cover an entire building. For Tremlett it is significant as his most public-facing work in a country where he has exhibited widely and is well-loved.

Keeping Time celebrates the unique story of the Cappella del Barolo twenty years after it was created. The idea of the chapel as a place intended for gatherings, hosting music and prayer, led us to consider LeWitt and Tremlett’s appreciation of music and its relationship to their practices. The compilation of tracks on the first vinyl looks at their work in terms of musicality and, delving into their own extensive music collections, finds affinities with the work of their friends and contemporaries. The second vinyl provides a point of access to LeWitt and Tremlett for a younger generation of artists whilst providing a platform for their work. A number of these artists participated in a related residency programme, the Mahler & LeWitt Studios in Spoleto; a town in Umbria where LeWitt lived throughout the 1980s, Tremlett visited, and both made work at the invitation of their Italian gallerist Marilena Bonomo. LeWitt’s studio and the stone sculptor Anna Mahler’s, as well as the Bonomo’s Eremo and Torre, are today used by a growing community of artists, composers, choreographers and writers for research and residencies. Some of the artists we have chosen to work with on this project have responded directly to the chapel or the musical context of LeWitt and Tremlett. Others more broadly relate through their exploratory combinations of visual art and architecture with music and performance.

In the 1970s, Tremlett made a number of sound works. His friend Gavin Bryars introduced him to loop-tape recording in 1970 and he would later collaborate with the New Zealander Tim Bowman to form some of his loops into an album entitled Hands up — Too Bad (2002). Both composers feature on the record. Tremlett listened to music avidly and a number of his pastel works, such as Drawings and Other Rubbish (1970) and Music to My (1978), reference specific songs or auditory themes. In some early text-based pieces he worked directly onto manuscript paper. The Spring Recordings (1972) document his travels through all eighty-one counties of England, Scotland and Wales. In each he made a recording lasting approximately fifteen minutes. With the exception of Greater London, each recording was made in quiet rural locations and consists of whatever could be heard at that time (principally wind and bird song). Tremlett said that ‘your field, or your hill, or your landscape is your studio’. His work presented sound as a serial, sculptural intervention by mapping it onto the geography of the national landscape. His slideshow No Title (1982) uses over thirty backing tracks and shows the breadth of his musical influences: jazz, lullaby, country, blues, a cappella folk, rock, and percussive African songs like Chemirocha III (1954) by Chemutoi Ketienya with Kipsigis girls, which we have chosen for the vinyl. Music and its patterns are always close to Tremlett’s work, expressed as perpetual feedback between the poetic potentiality of landscape and the structure of architecture.

LeWitt described listening to music as experiencing ‘form in time’. Like Tremlett, he played music in his studio as he worked. He copied his vinyl collection to cassette so he wouldn’t have to flip records with grubby hands. His extensive collection of cassettes, predominately classical, fills an entire room in his Connecticut home and is methodically catalogued in a hand-written logbook. He was vocal about the influence of music on his serial art and he listened attentively to different recordings of the same composition; his logbook has sixteen pages devoted to Bach. In reference to one of his earliest wall drawings, Wall Drawing #26 (1969), a version of which we are installing for the Keeping Time exhibition, LeWitt, describing the relationship between his instructions and the drafters who execute them, said with characteristic generosity, ‘I think of it more like a composer who writes notes, and then a pianist plays the notes, but within that kind of situation, there’s ample room for both to make a statement of their own.’ LeWitt was friends with Steve Reich and Philip Glass and supported them before they came to recognition by purchasing their hand-written scores. One such acquisition by LeWitt allowed Reich to afford the drums for Drumming (1970-71). LeWitt and Glass worked together on Dance (1979), with Lucinda Childs. Both Reich and Glass appear on our first record, and the affinities between their work — in regard to repetition and variation within a self-imposed system — and that of LeWitt and Tremlett are evident.

With the chapel in mind, several tracks express the intrinsic and dynamic relationship that exists between sound and architecture. Cage du Grand Escalier (1993) by Gavin Bryars explores the acoustics of the vast spiral staircase in the Château d’Oiron in France: For the recording, he placed his musicians at intervals along the staircase from top to bottom. We felt that the materials Caroline Shaw references in Limestone & Felt (2012) neatly reflect the surfaces of the Cappella del Barolo: whilst LeWitt’s variations of hard-edged, bold colours contrast with the landscape and proudly announce the chapel as an architectural surface, Tremlett’s interior is of a softer nature. In places, the pastel work brings the landscape inside, dissolving the architecture.

All remaining tracks were specially commissioned for Keeping Time. James Cave’s The Point on the Arch Mid-Way Between the Two Walls (2019) continues on the architectural theme and brings the Torre Bonomo and its artworks in Spoleto, where he spent time as composer-in-residence in 2016, into dialogue with the chapel. Appropriate Energy (2019) by Keef Winter redeploys some of Tremlett’s loop-tapes, manipulating them to find a twenty- first-century rhythm. By way of Tremlett, LeWitt and Laurie Anderson, Adam Gibbons’s conceptual piece Intro O (2019) examines the nature of the loop and poses questions about the communicative capacity of art and language. From his Harlem home in New York, Jason Moran imagines a conversation with the landscape of La Langhe by sipping wine made from its grapes (If The Land Could Tell, 2019).

Moran’s track sketches out a terrain for music which is inherently transgressive: by its nature, sound will not be constrained by borders, it is dynamic, relational and social. Following this train of thought, Hiba Ismail’s tracks SUNKAB and examine the acoustics and architectonics of public space in Sudan. She finds a kind of sonic resistance in the cohesive, rhythmic sounds made by street protesters and the more domestic sound of a pestle and mortar grinding coffee beans. Similarly, Lydia Ourahmane’s Akfadou (2019) compiles audio jottings from her daily life which pose questions about our sense of belonging in a global geography marked by the restriction of movement. Babatunde Doherty’s Itinerant’s Creed (2019) reworks loop-tapes by Tremlett whilst imagining the trials of a displaced maritime wayfarer.

From its indeterminate beginnings, the Cappella del Barolo found a new lease of life as a site specific artwork: today its walls welcome all creeds and colours, reflecting the joie de vivre of a group of holidaymakers as readily as the reflective mood of a solitary pilgrim. It is a generative place. In compiling these records, we sought to follow the example of Bruno Ceretto’s open-minded invitation to LeWitt and Tremlett in 1999. Woven through the work of those two artists and their contemporaries, a group of younger artists has been offered a space (minutes on the vinyl) and a context (the chapel) with which to work. Their free responses give form to a compilation full of new dialogues which create unexpected links across disciplines, generations and geographies. Buon ascolta.